The stories behind 2 tunes by Katie Howson

Updated with additions January 2021

The following articles about tunes played by traditional musicians from East Anglia appeared in EATMT newsletters from 2011 onwards.

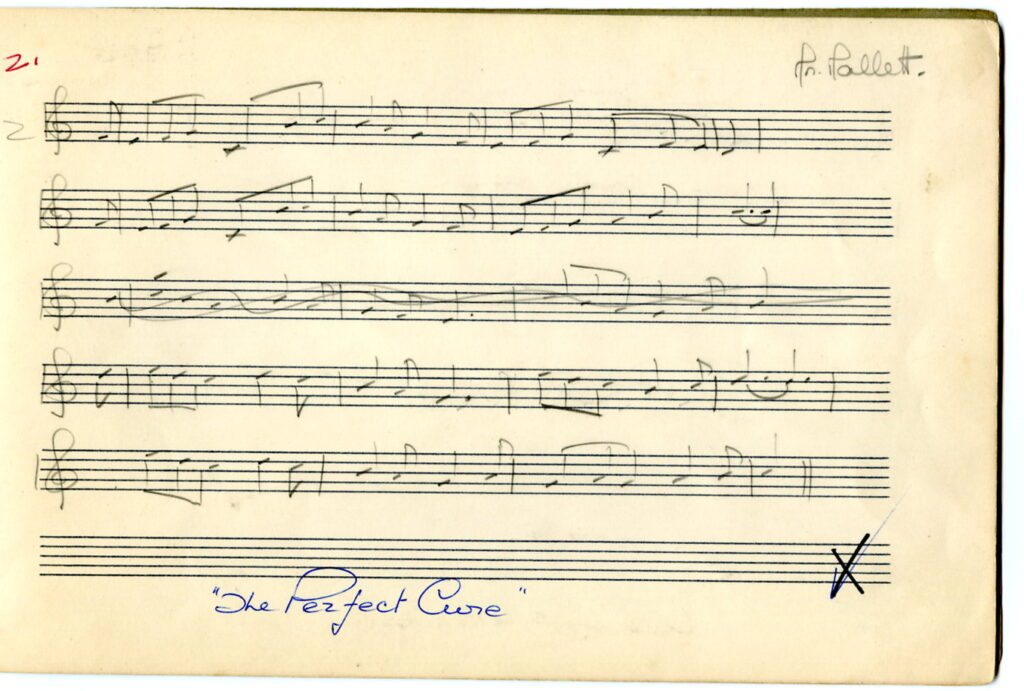

Tracing a Tune No.1 – The Perfect Cure

The Perfect Cure is often thought of as a quintessential Norfolk tune, one of several jigs collected in the county that were played for the Long Dance. As so often, a little bit of musical archaeology reveals not only other regions that see the tune as being distinctively theirs, but also a glimpse of the way melodies moved between different performing contexts in an era before tunes tended to be pigeon-holed into different genres. The strength of the Norfolk connection comes from the fact that it was published by the English Folk Dance and Song Society: first in ‘The Coronation Country Dance Book’ in 1937, a year or so after it had been noted down from melodeon player Herbert Mallett of Aldborough by Joan Roe, and with a longer lasting influence, in ‘The Fiddler’s Tune Book’ Vol 2 in 1954.

In July 1950, Herbert Mallett visited the BBC studios in Norwich and recorded several items including The Perfect Cure. The EFDSS Vaughan Williams Memorial Library holds the acetate recordings and this tune and others can be heard on the Musical Traditions website, in Chris Holderness’s article about Herbert Mallett (pictured left).

Dulcimer player Billy Cooper from Hingham also played it, with a slightly different B music, but it is Mallett’s version which has become the standard English version of the tune in modern times.

Several years ago, Con O’Drisceoil from County Cork was a tutor at Melodeons and More, and in the concert, he introduced a tune that he considered to be one of the more unusual items in his local Sliabh Luachra repertoire, a 12:8 jig (known as a slide), which turned out to be –The Perfect Cure! It goes by a couple of different names there: She Hasn’t the Things She Thought She Had and Behind the Bush.

Further research has turned up a set of words, noted down from the Oxfordshire fiddler Sam Bennett in 1950:

‘The cure, the cure, the perfect cure, you are a perfect cure,

And all at once the maid she cried, You are a perfect cure!

Some got trampled underfoot, some crushed beneath the wheel,

Lord how the parson he did curse and how the pigs did squeal!’

The phrase ‘perfect cure’ was a slang phrase, current from the mid nineteenth century, for an eccentric and amusing person. The original song dates from that period, and consisted of ten verses written in 1861 by F.C. Perry. The song was a roaring success in the Music Halls, made popular by James Hurst Stead, who, after the final verse, went straight into an early version of the punk pogo dance, where he is said to have jumped up and down 400 times during the song, and sometimes performed it in four different venues in the course of one night!

The actual melody, composed by Jonathan Blewitt, predates this set of words, as it was originally written for a song called The Monkey and the Nuts. The original tune was written as a schottische although it is now commonly played as a jig. Prior to the folk revival, there were a number of such tunes (e.g. Woodland Flowers), usually referred to as barn dances, which were half-way between a jig and a schottische. They were popular for the Long Dance in Norfolk and Herbert Mallett played at least one other tune in this timing, the title and history of which remains to be identified.

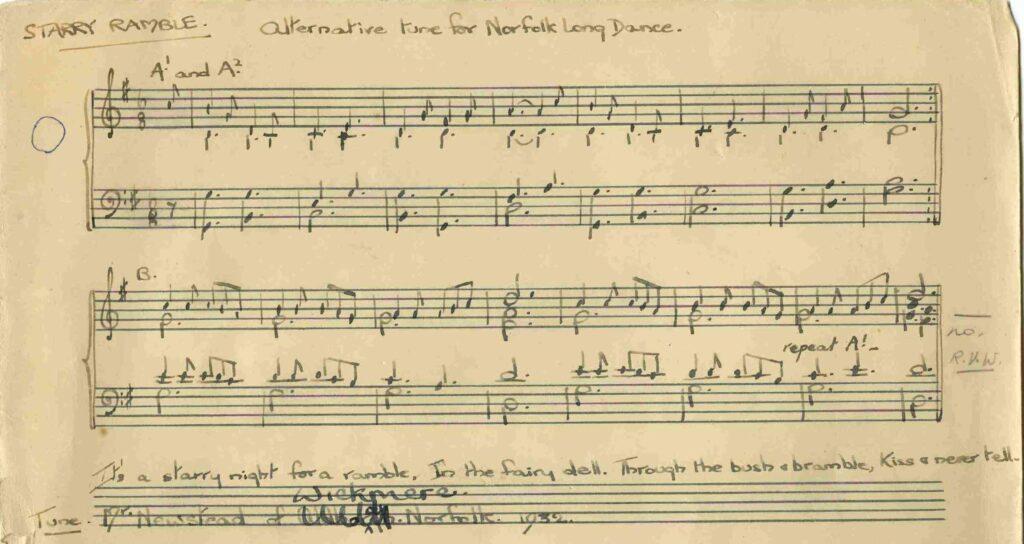

Tracing a Tune No.2 – Starry Night for a Ramble

The tune Starry Night for a Ramble has been an old stalwart of the southern English repertoire since the revival spearheaded by Rod Stradling and the Old Swan Band in the late 1970s, although at least two distinct versions have now developed even in that short space of time and context.

It has been collected from two traditional musicians in England – both from Norfolk: it was noted down from Mr Newstead in Wickmere in 1932 by Mrs Gay and subsequently published in “The Fiddler’s Tunebook Vol 2” and the tune was also recorded by Peter Kennedy from the playing of Herbert Smith from Blakeney, titled ‘Starry Night for a Randy‘. Herbert’s version of this tune, Chris Holderness writes in his article in Musical Traditions, is considerably different from the better known one that was collected from Mr Newstead. The article on Herbert Smith on the Musical Traditions website also contains the sound file of a BBC recording by Peter Kennedy in 1952, of Herbert’s playing of Starry Night for a Ramble which you can access HERE. Some of these 1952 recordings of Peter Kennedy (including Herbert Smith’s Starry Night For a Ramble appear on the Folktrax CD (FTX328) Rig-a-Ji-Jig Norfolk Village Music.

We published Herbert Smith’s version in our 2007 tune book ‘Before the Night Was Out‘.

Another Norfolk connection is given in the book ‘I Walked by Night‘ – the autobiography of Frederick Rolfe, an inveterate poacher, even during his occasional spells of employment as a gamekeeper. Rolfe lived most of his life in the King’s Lynn area of west Norfolk. Rolfe’s book (published in 1935) gives the following words under the title The Ploughboy’s Song:

A starry night for a ramble, in the flowery dell,

Through the bush and bramble, kiss and never tell.

I like to take my sweetheart out (“Of course you do”, says she)

And softly whisper in her ear, “How dearly I love thee”.

When you picture to yourself a scene of such delight,

Who would not take a ramble on a starry night

The tune and lyrics were actually published in 1873, composed by Samuel Bagnall, and the song was recorded by Arthur Collins and Canadian tenor Harry McDonough in the early twentieth century. It is likely that these publications and early recordings were actually the sources for ‘traditional’ musicians, although in earlier days, when songs were printed on broadsides, they had sometimes, in fact, been “collected” from singers, and it is less clear where the source might lie.

Interestingly, the tune Starry Night for a Ramble has been far more popular than the song, and it has been interpreted in different rhythms: the original publication was in 6/8 timing, which is how it is still known in the East Anglian and broader English traditions. There’s also a tune by the same title, again a jig, which is used in the US as a contradance tune. The same melody was popularised in 3/4 timing by Aly Bain and Phil Cunningham, as Starry Night in Shetland and, under its original title, Australian collector John Meredith found that ‘nearly every bush musician plays this beautiful waltz’ although he only collected lyrics to it on one occasion (“Folk Songs of Australia”). There’s also a lovely recording of Tasmanian fiddler Eileen McCoy playing it on the CD ‘Apple Isle Fiddler’.

Both of these tunes form part of a track by the Catfield Trio on the Sinkers and Swimmers CD QCD 0501.