Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1812

Printed and sold by J. Gray, Bury St Edmunds

Written by Katie Howson, co-founder of EATMT, November 2012.

Twenty ago when researching dancing and music in Suffolk in the nineteenth century, I became aware of a small collection of dances and tunes published in Bury St Edmunds.

The booklet is called “Twenty Four Dances for the Year 1812†and was “printed and sold by J. Grayâ€. Other such collections were published from the middle of the eighteenth century, including some published by the London based printers Thompson, whose 1803 and 1805 editions state the dances or tunes to be “composed by Mr. Gray” suggesting that he was well known at the time. So far, all the known comparable collections were published in London and occasionally other large centres of population. This one is rare in being printed in a provincial town, in showing the composers of individual items, and being of a late date: in 1812 the popularity of country dances was soon to wane as they were overshadowed by quadrilles and couple dances such as the waltz, polka and schottische. For a wider view of such publications, there is a listing of historical manuscripts on the Folkopedia website.

Dance instructions (without music) were often included in Ladies’ Almanacs from the period as well; for example, the Bury and Norwich Post from 23rd November 1814 includes an advertisement for Rackham’s Country and Town Ladies’ Memorandum Book containing 100 new country dances.

Thanks to Dave Burt from Norton, I was able to examine an original copy, which always gives me a shiver down the spine! This particular copy seems to have been owned by members of a family named Emmerson, from Trumpington near Cambridge, and possibly Brown from Earith, judging from handwritten notes on the brown paper cover which has been handstitched outside the original printed cover.

The Dances and Tunes

The dances themselves are virtually all of the longways duple minor format so prevalent at the time, and are variations on a small number of figures.

The selection of tunes is more unusual and ten of the twenty four tunes appear to have been composed by local musicians: JG (Gray), J. Reeve, SP (unknown) and JC (Crask).

INDEX (Click to access the index)

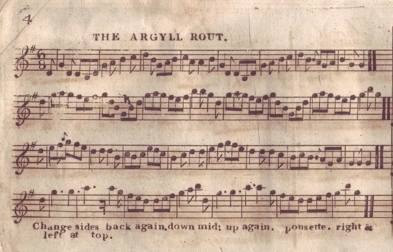

The tunes are indexed here. From the index you can click through and look at the dance instructions and musical scores for each title. Here’s one as taster – the Argyll Rout, which makes a good driving jig for contemporary ceilidh dancing. It’s already in the key of G, which is not too bad for fiddle and melodeon, although it does go pretty high, and is usually played today in the key of D. On the main page, we will offer some transposed versions as well as showing you the originals.

How these tunes were in use beyond the publication date cannot be surmised, and very little collecting of instrumental music was done in the area. There’s certainly no trace of this sort of music in the repertoires of “traditional†players recorded in the mid twentieth century. In King’s Lynn in Norfolk, Ralph Vaughan Williams noted down tunes from Stephen Poll in 1905, who played as a solo musician for dancing at fairs throughout the late nineteenth century, but so little is known of his repertoire or playing contexts, that it is not possible to extrapolate significant information from this.

These days, in folk music circles, tunes from early 19th century manuscripts generate lots of interest and are played alongside the popular repertoire that was played by more recent musicians such as Oscar Woods, Percy Brown or Scan Tester from Sussex. The book and CD set “Hardcore English†published by EFDSS in 2007 gives a good overview of the contemporary repertoire of English players, encompassing both historical and traditional sources.

The Local Musicians

Over the course of this year I have followed up the initial research in some depth, and have failed to identify or unearth any details about the “main man†J. Gray. The front cover states that he printed and sold the booklet and he is also the composer of The Bury Volunteers Hornpipe and Miss Teptop’s Reel. Despite painstaking and wide-ranging research, I have found no trace of Gray in any local records as a musician, printer or in any related trade. There are a couple of farflung possibilities, but no identification has been possible from the evidence so far. The most tantalising snippet of information is that the organ in St Mary’s in Bury was built and installed by one John Gray, a famous organbuilder based in London, in 1826.

There is no trace of the book’s publication in the newspaper advertisements of the time either, suggesting the possibility of a private publication. Analysis of the print itself shows it has been roughly trimmed so that some page numbers may be seen upside down at the edges of other pages. The fonts used for titles vary: although it’s not completely consistent, the local tunes mostly have block capitals and the wider known tunes using a flowing cursive script: one theory is that these were bought in ready printed and the local tunes added to them in Bury. Poor print quality is especially noticeable in the dance instructions, where the alignment and spacing of the letters is very inconsistent, suggesting Gray was perhaps an enthusiastic amateur with access to some printing equipment. Looking at comparable printed collections (E.g. Thompson – see above) they all have a similar printed style, so this latter theory may not be so likely.

Of the other contributors, S.P. (Frank Oatland’s Waltz, Epsom Lass and Story Gate) is unidentified and J.Crask (Hamton Court Frolicks and The R.L. Spencer) is thought to be John Crask(e), born 1759 in Bury St Edmunds. There are indications that he was a music or dancing teacher and his son George went on to be a violin maker in northwestern England.

Another of the composers, John Reeve (see references in the next section too), has proved much easier to research, as his family were involved in music professionally in Bury St Edmunds for over a hundred years. There were at least four generations of John Reeves; “our†John Reeve is most likely to have been born in 1783 and died in 1854. He taught music, played in orchestras and ran a retail business selling sheet music, books and musical instruments. For many years the business was in Crown Street, near the Abbey, and later moved to Abbeygate Street. His son John continued the family business on Angel Hill.

A newspaper advertisement from 1814 includes “pianofortes tuned, which he can leather the hammers of†and “music provided for Balls and Assemblies on the shortest notice.â€

In 1826, with a growing family to support, Reeve arranged a “Juvenile Concert†for the benefit of his children. They played a varied programme of items by Haydn, Corelli, Mozart, Weber and Parry on violin, viola, violincello, flute, harp and piano. John Reeve junior was at the time studying at the Royal Academy in London. Such concerts were regular features of the cultural life in towns at the time; a later one advertised in February 1834 to take place in Sudbury, did not include John Reeve junior who worked as a music teacher in King’s Lynn around that period.

Cultural Background

Most of the research in this section was undertaken for an unpublished thesis “Dancing in Suffolk 1780-1850†for an Advanced Diploma in Local History in 1994/5, awarded by the Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education. Information about assemblies nationally can be found in Chapter 7 of Mark Girouard’s book “The English Town†(1990). James Oakes’ diaries were edited by Jane Fiske and published in two volumes by the Suffolk Record Society (1991).

From the early eighteenth century, cultural activities developed and flourished in provincial centres such as Bury St Edmunds: dancing was central to the social scene and an essential part of a middle or upper class upbringing was learning the steps and manners of dances. At the time of this publication, a dance programme would sometimes still include the minuet, which continued as an opening dance until the second decade of the century, but would mostly consist of the longways “country dances†dominant until quadrilles came into fashion. The Ipswich Journal of 27th December 1819 advertised “Country Dances and Quadrilles to be danced alternatelyâ€.

Dancing took place at public events such as the balls held in Assembly Rooms and LongRooms (usually attached to taverns) and at private parties (often called “Routsâ€).

Bury St Edmunds was a leading centre of provincial culture and the Assembly Rooms built there in the early eighteenth century influenced developments in Norwich and Ipswich. The Athaeneum was completely refurbished in the early eighteen hundreds and afterwards described as ‘an elegant structure, so highly ornamental to the town’ (Eric Gillingwater, “An Historic and Descriptive Account of St Edmundsburyâ€, 1804). The Adam style ballroom (actually designed by Francis Sandys) from that renovation remains today, with a musician’s alcove to one side and a grand double staircase leading up to the rooms used for refreshments and playing cards (see right)

Public dances in Bury St Edmunds

In Bury St Edmunds, the public dances were usually held on Thursdays during the winter months and at times when there were other important events going on, such as the Assizes and the annual October fair, when people would travel in from surrounding smaller towns and villages and some of the local gentry might be in town. Theatrical productions also followed a similar schedule.

Bury was assiduously praised throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, for its ‘open and extensive prospect’ and ‘the uniformity of its buildings, the regular situation of the streets, which in general cut each other at right angles.’ (Frederic Shoberl, “The Beauties of England and Wales†Vol XIV, 1813. With the winter season of subscription balls and the regular social events surrounding Assizes week in addition to the Fair held every October, Bury gained a reputation for social exclusivity, as a further comment from Frederic Shoberl shows: ‘It has been universally remarked, that there is not perhaps a town in the kingdom, where the pride of birth, even though conjoined with poverty, is so tenaciously and so ridiculously maintained as at Bury.’

In 1814, the Bury & Norwich Post carried a host of advertisements for amusements available during Bury Fair week. This included shows at the theatre, which opened approximately a dozen times in October and early November. Three assemblies during Bury Fair week was fairly typical in the early nineteenth century, although back in the 1780s there had often been five, and by 1850 they had died out completely. The price structure for the balls indicates that the Friday night was the biggest event. The ball advertisements inevitably include the phrase ‘the Nobility and Gentry are informed’ – a fairly standard form used for advertising any function of these kinds. Combined with the high admission prices, the intention to exclude tradesmen and general riffraff is quite clear.

At public balls, there were often stringent rules set down for behaviour, and sometimes entrance was by subscription or invitation only. As the century continued, separate events began to be advertised for tradesmen, for example, in 1816, there were two balls held in the first week of January at the King’s Head in Diss, one described as a “Farmers and Tradesmen’s Ball†and the other as an “Assemblyâ€. The former was an annual event and the latter part of a regular round of events organised in Diss, Eye and Scole. James Oakes, a banker from Bury St Edmunds noted a “2d ball for the Inhabitants at large†to be held in 1798 on the occasion of a great naval victory.

Evidence of what the public balls were like is tantalisingly rare, but the following examples give a taste of the social atmosphere.

‘There will be eight Assemblies on the Thursday nearest the Full Moon, in the months of January, February, March, April, September, October, November and December, of which a list will be given in this paper of next week.

‘Every subscriber, for him or herself singly to pay One Guinea, for the above eight nights, tea included.

‘Subscribers paying Two Guineas may introduce the ladies of his or her family, and ladies resident in such family, or visiting there, and who do not live within six miles of Ipswich, the above eight nights, tea included.

‘Non-subscribers to pay four shillings each, tea included.

‘No person cam be admitted into the ball-room until the subscription under which he or she comes, be paid; nor any servant, upon any pretence whatever, except those of the house.

‘N.B. The room to be lighted up in the same manner as for the King and Queen’s birthdays.’

(Ipswich Journal 16th December 1780)

‘Friday May 7th 1802

At Evening a general Peace Ball, the Number present reckond 345. There were eight Stewards: the Recorder, Mr Bunbury, Mr Blachley, Mr Oakes, Mr Smith, Mr Squires, Mr Browne, Mr Jerkins. The Room divided by Form into 4 equal Divisions for the Country Dancers, say abt 15 in each, the whole 60 couple. The Tickets 3/6 each, Tea included.’

‘Wednesday March 10th 1819

We had a fifth Ball open not only to Subscribers but to all Ladys & Gentlemen (not upon Subscription), but everyone paid: the Gents 10/6 & Ladys 7/6 with Supper as usual. It was very genteely attended, all the first Familys in the Town & Neighbourhood, full 120 – say 24 couples, some part in 2 sets.’

(James Oakes’ diary)

The ’20 Cambridge Gentlemen’ in the 1819 extract, although apparently acceptable on this occasion, are at other times complained about as upsetting the balance of ladies and gentlemen for dancing. Their presence hints at the attractions of Bury as a social centre.

Private dances in Bury St Edmunds

James Oakes’ diary is also full of references to dancing in private homes, especially through the 1780s and 90s when his children were young, for example on Friday 23rd January, he describes “A Ball at Mr R. Adamson for our young Ones … All danc’d makg up abt 8 or 9 couple. A very elegant supper; 4 Dances after & got Home soon after 2 o’clock.â€

The unpublished autobiography of Mrs J Gilbert, written in 1874, recalling her youth in Lavenham in the early 1800s is in the Suffolk Record Office and charmingly records the differences in expectation between the upper classes and aspiring farmers’ families, at a private dance held by the Coe family at their farmhouse:

“No less than sixty rural belles and beaux assembled. The chamber of arrival was thickly strewn with curl-papers, my own hair was dressed as a wig two or three inches deep, hanging far down the back and covering the shoulders from side-to-side … perhaps I had better confess that, though having learned to dance – an advantage not general to the company – I might have expected some appreciation as a partner, the full-formed easy figures, glowing complexions and merry eyes of the farmers’ daughters, were undeniably more in request.â€

Music and Musicians in Bury St Edmunds

All these occasions required live music, perhaps just a couple of people for a private party, or a full band for a public dance for three or four hundred people at the height of the season, without the benefit of any amplification, of course. Newspaper advertisements for balls do not mention bands or musicians by name until the 1830s. James Oakes mentions some musicians involved in playing in private houses by name: James Harrington (a musician and dancing master) over a number of years, in 1811, “Craskin & his Brorâ€, who may well be the J.Crask from the Gray booklet; in 1818, “Reeve’s Bror one violin†and in 1820 “Mr Reeve played by himself the whole Eveng. I gave him one guinea.†Sometimes music was provided within the family circle, on harpsichord or other instruments unknown. On January 1st 1813. Oakes held a family party with 25 couples dancing and 5 musicians. The next day he noted “The Wheights called for an Xmas Box. We had them to play and made a dance for the young Ones. 7 or 8 couple for a couple of hours before Tea.†The Waits were small groups of musicians, established in the fourteenth or fifteenth centuries, who played for civic events including chairing in election winners etc. By 1813 their function had been eroded greatly so that most had been disbanded long before, and the few remaining ones disappeared with the 1834 local government reforms. This example is a rare citing of them in the nineteenth century.

James Oakes was also involved in organising public dances in Bury, at both the Assembly Rooms, where he became a shareholder in 1801, and the Guildhall. He evidently held a financial role and in 1785 noted a fee of £1 & 6d paid to the musicians – 2 violins and a tabor. This is well under the cost of 19 bottles of wine and 12 bottles of beer at £1 15s 9d for the company of just under 40 people. In the same year he also noted that a London band was engaged for the subscription balls at a fee of seven guineas – it’s not clear if that was for one event or the series. In 1795 he recorded that the “Musick†received a fee of 15s 6d, and further collection from 10 gentlemen of 10s 6d; at a charitable ball in 1796, the “Musick†received 31s 6d and 15/- worth of “liquorâ€. The term “Musick†may refer again to the Waits.

A number of the tune and dance titles in the Gray collection refer to military characters or groups. This period was one with many military campaigns – the Napoleonic and Pensinsular Wars and the War of 1812 all meant that many numbers of soldiers were needed, and voluntary militia groups were established all over the country. In addition, the presence of various regiments for prolonged periods in barracks and temporary encampments meant there were more young men around, and also more musicians: performances by regimental bands were regular additions to the cultural life in Bury and Ipswich. At least one musical item from the Gray collection is still played by military bands today – the Argyll Rout, although possibly not under this title. Others may also have had another existence within theatrical productions – possibly Frank Oatland’s Waltz in this collection.