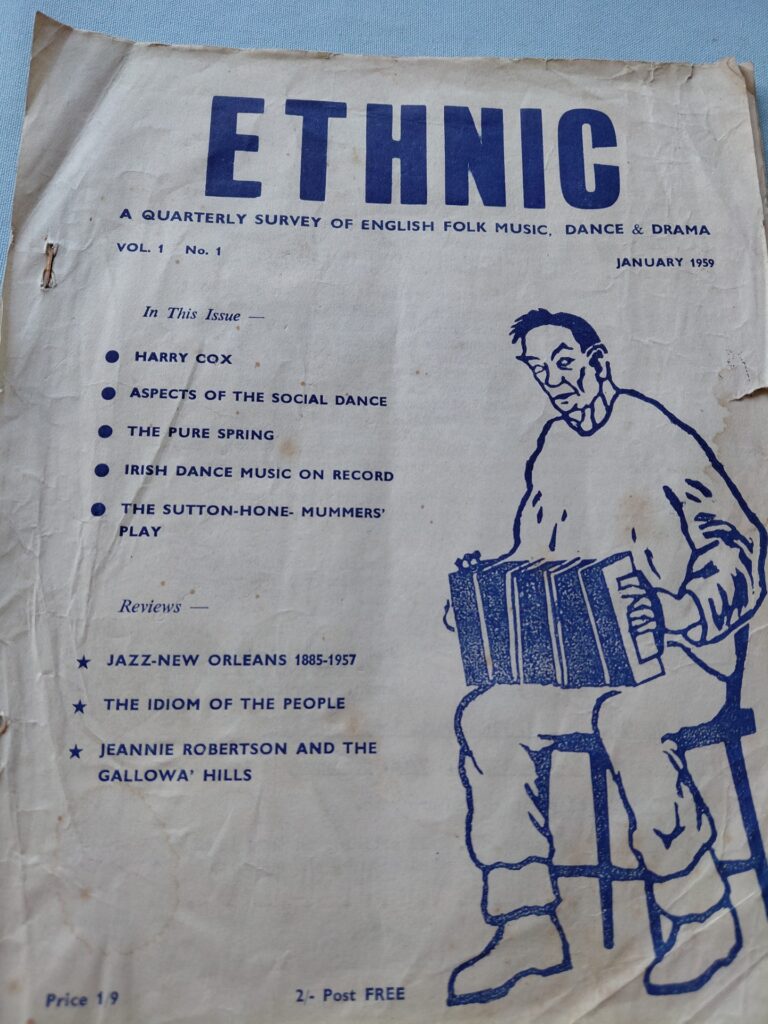

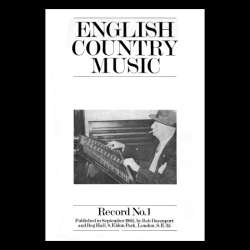

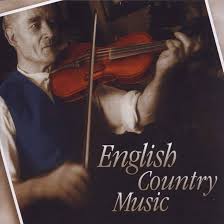

Sixty years of the legendary record

It is sixty years since the legendary English Country Music album was released as a private pressing, limited to 99 copies, as Record No 1, by Reg Hall and Bob Davenport. The LP was reissued more widely by Topic Records in 1976 (1) and then again, in greatly expanded form, on compact disc in 2000. (2) This situation alone demonstrates the enduring significance and influence of the record, particularly on the revival of interest in English instrumental music and dance tunes. An inauspicious start perhaps for a disc with which Reg Hall was taking chances by releasing a selection of recordings he and Mervyn Plunkett had made with Walter and Daisy Bulwer and Billy Cooper in 1962.

It is difficult to imagine now just how little information and how few recordings were available to enthusiasts sixty years ago, particularly to those of us too young to remember the situation first hand. The ‘renaissance’ of interest in traditional music in the 1970s, on both sides of the Atlantic, leading to the regular and sumptuous issues of traditional material by labels such as Topic and Leader in Britain, and Folkways and Rounder in the United States, not to mention the countless smaller concerns, were in the future. Most of these issues were exemplary in their packaging, with copious notes and photographs, providing a richness that went further than just what was contained in the grooves of the record. More recently, of course, despite the small audience for such music, a great deal has been issued on compact disc, with the same attention to detail and information, and continues to be so. In 1965 there was little available in Britain, a few limited-edition releases by the English Folk Dance and Song Society, and a few EPs of songs. Topic Records had begun to dip their toe into the water, with LPs by Jeannie Robertson, the Willett Family and Joe Heaney, but nobody had considered putting out a disc of traditional instrumental music: as Reg Hall stated in the CD booklet: “Topic was not ready for our sort of music” and wasn’t interested in releasing it.

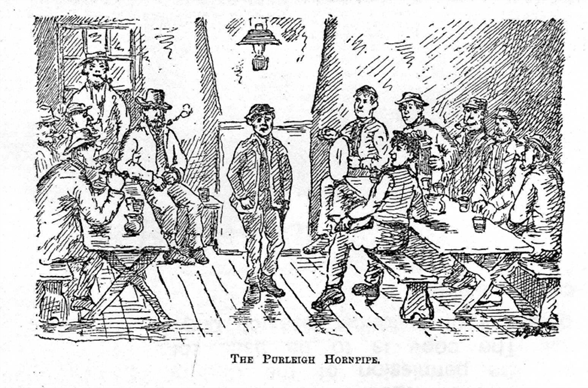

To go back a few years, Reg Hall and Mervyn Plunkett, as enthusiasts for English traditional music, had started the West Hoathly Band of Music in Sussex, with several local traditional performers, including the formidable Scan Tester (3) in 1957. This band seems to have had a fluid line-up and some riotous nights in various pubs in that county and, as Reg related, “In October 1957 Mervyn arranged a coach trip to London. We entered Pop Maynard, Jean Hopkins, George Spicer, Bill Hawkes (4) and the full band in a competitive festival at Cecil Sharp House, headquarters of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. We shocked many of the people there and confused some of the adjudicators, who were used to genteel settings of folk songs… Very few of the audience had ever heard a country singer before, and even fewer had ever heard country pub music. Some of them, it seemed, were excited about it.” (5)

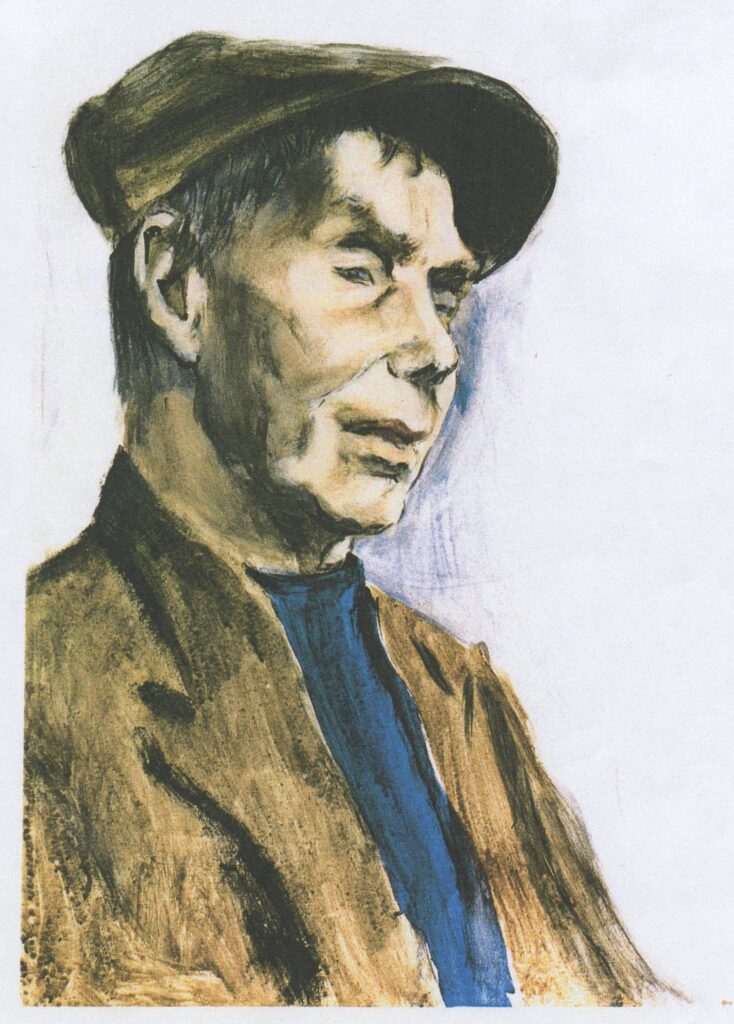

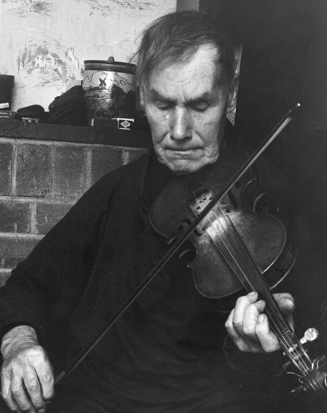

Mervyn Plunkett’s job as a salesman took him around the country and it was here that he came into contact with Walter Bulwer of Shipdham in Norfolk – the full story is related by Reg Hall in the CD booklet notes. Mervyn visited Walter and Daisy Bulwer several times and recorded Walter’s fiddle and mandolin-banjo playing in March 1959. (6) On 12 April of that year Reg accompanied Mervyn on a visit and “within minutes of the introduction, we were playing some of Walter’s tunes together. To our great amazement and delight, Walter soon left the lead to me and broke loose on some surprising and inventive second parts.” (7) The stage was set, particularly as Walter suggested that Mervyn should approach Billy Cooper, of nearby Hingham. Reg elaborates on this: “I got the impression, when we eventually brought them together, that they didn’t know each other, which now upon reflection seems very unlikely.” (8) In fact, Sam Steele had recorded the Bulwers and Billy Cooper playing together at some point between 1959 and 1962, on which occasion they certainly sound as if they were used to playing together (9).

The various participants met at the Bulwers’ cottage twice in 1960, in January and April, to record material. Due to several circumstances – Reg Hall again gives details in the CD booklet – these were not successful. Of these occasions, Reg comments: “Up until then our motives had been largely to do with the excitement of discovering the talents and inventiveness of the older musicians we had met and the fun of playing together. Very few people connected in any way with the folk-dance movement had not even the slightest notion of the existence of traditional instrumental music, and most commercial recordings of English country-dance were, to put it mildly, gutless” and that there was “our determination to make some sort of contribution to the world’s awareness and understanding of traditional music.” (10)

“The Saturday of the August Bank Holiday weekend in 1962 saw us all back together again; this time with Bill Leader recording for Topic Records.” (11) Mervyn Plunkett urged Russell Wortley to join in with his pipe-and-tabor, “to add tonal quality to the upper register.” On the second day Billy Cooper wasn’t available and “without him the band took on a quite different character.” For the second day, Harry Cox had also been brought along by Mervyn, but he “was, of course, a much rougher musician used to playing in his own time and rhythm and, not being able to make much of our way of playing, soon put his fiddle down. He enjoyed the rest of the day, however, listening to the music and joining in the banter.”

“We opened up the first session with our signature tune, Jenny Lind and The Girl I Left Behind Me.” (12) What followed was a series of polkas, waltzes, schottisches and hornpipes. Reg Hall gives a full account in the CD booklet, and I don’t propose to reproduce all of that here. Suffice to say that enough material had been gathered to consider an LP record, which Bill Leader was happy to edit, Reg having selected the performances with “the best starts and finishes, and the fewest mistakes”. (13) As has already been mentioned, Topic Records wasn’t interested in releasing the material and so Reg Hall and Bob Davenport prepared “a limited-edition long-playing record, which we issued in September 1965 as Record No.1 on our nameless label as the first of a series on a subscription basis. For tax reasons we could only make ninety-nine copies and surprisingly they were sold out in a fortnight.” (14)

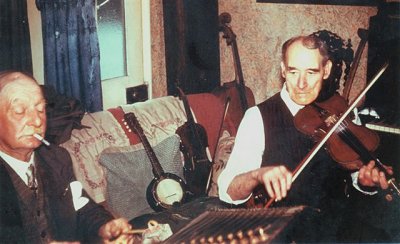

For this limited release LP, thirteen tracks were selected from the sessions. A mixture of polka tunes, both obscure and un-named and well-known, such as Bluebell Polka, the jig Off She Goes (with an unusual second strain), two sets of medleys of waltz tunes, schottisches and well-known standard country dance tunes such as Jenny Lind Polka / Girl I Left Behind Me and The Four Hand Reel / Soldier’s Joy. In short, a good sample of the stock-in-trade of a southern English country musician, all with an infectious ready-to-dance jauntiness and loose ‘down-home’ feel. The LP concluded with an example of a tune Walter picked up when playing briefly for a morris side locally, Shepherd’s Hey. (15) Walter (fiddle and mandolin-banjo) and Daisy Bulwer (piano) and Billy Cooper (dulcimer), of the older generation, were joined by Reg Hall (melodeon and fiddle), Mervyn Plunkett (drums) and Russell Wortley (pipe-and-tabor) for what became an iconic sound and an inspiration for countless musicians later on.

This influence was not immediately apparent, however, and Reg Hall continues in the notes to point out that “Our exposure of Walter, Daisy and Billy to a larger world did not bring much interest to their doorsteps. Billy was dead by the time the record came out, but Walter and Daisy were pleased to receive visits from some younger musicians.” (16) However in 1974 Topic did use a couple of tracks from the sessions on their Boscastle Breakdown LP of southern English instrumental music and in 1976 the same label reissued Record No.1 as English Country Music. (17) Reg points out that the record had become a model for a new generation of musicians all over England, a couple of untitled polkas becoming particular favourites (18), much to his surprise, as being “too far removed from modern taste – even modern taste in traditional music.” (19)

In fact, it was just these polkas that attracted some musicians in the burgeoning English country music scene (of instrumentalists wishing to explore the range of traditional English country dance music), as Rod Stradling, leading light in that scene as a member of Oak and the The Old Swan Band, recalls: “I think that something I wrote in a review of Record No 1 English Country Music, when it was re-released on Topic in 2000, rather sums up the way I, and perhaps others, felt about our discovery of traditional English dance music back in the late-Sixties. In the Notes to the Topic release Reg Hall wrote that he was surprised that Walter Bulwer’s Untitled Polka should have become a favourite of the young English country music revival, since he felt that it was ‘so far removed from modern taste – even modern taste in traditional music’.

“My response was that: its appeal, apart from being a great tune, was precisely that it was ‘so far removed from modern taste’. We were, I think, unconsciously looking for ways to reclaim some sort of identity and cultural heritage in the face of the increasing Americanisation of our world – and the rising tide of badly-played Irish music amongst our English contemporaries. And it was precisely because it wasn’t one of the pop-song

tunes of our parents’ generation, who had left us a legacy of world wars, the Holocaust, rationing, austerity, nuclear threat, sexual repression (the list seemed endless) that caused it to appeal so strongly to us. We picked on that tune particularly, for the same set of complicated reasons that we preferred (say) Fred Jordan to Martin Carthy or – more apposite – Bampton to Headington.

“But the fact that the music and the players were available to us provided a focus for the undefined yearnings for a music we could call our own. Almost uniquely, at that time, it was something we could fight for – whereas our adult experience of the world prior to that had been defined by our fighting against things.” (20)

So, influential and important indeed! It is certainly true that several of the tunes have endured well in the folk revival, particularly when a few more tracks were issued on the Topic LP Boscastle Breakdown in 1974 (as well as the reissue of Record No 1 in 1976). (21) A couple of untitled polkas in particular have become favourites, as alluded to by Rod Stradling above, although not always played in the style – or the keys – of Walter, et al. (22)

Katie Howson, co-founder of EATMT, had this to say: “Right from the opening bars of the first track I have always found this recording very exciting, and it still gives me goosebumps! Jenny Lind in one key led by Reg Hall on melodeon, Billy Cooper on dulcimer and Walter Bulwer on fiddle: simple and direct music that gets you in the guts and makes your feet move. I can remember how the scratchy fiddle playing, background coughing and slightly random accompaniment all added to the charm and seemed to make it somehow exotic, whilst at the same time being totally rooted in the locality.

“I would have heard this LP in 1977 or 78, before I moved to Suffolk, and this album (“the black album”) and English Country Music from East Anglia on the Topic label (“the white album”) were two things that made me want to move here and hear similar music in situ. Of course, by that time Walter Bulwer and Billy Cooper had died, but I was able to meet Billy Bennington, Oscar Woods and Harold Covill from “the white album” in person, and indeed become pals with Billy and Oscar.

“I also count myself exceptionally privileged to have spent much time with Reg Hall, one of the leading lights behind this recording. Over the course of five decades I have spent hours playing music with Reg – both English and Irish – and have had many long conversations with him about musical (and other) matters. He is known for his profound knowledge, writings and CD compilations for the Topic label and others, but his influence as a musician sometimes goes unrecognised and I would like to put on record here the huge inspiration he has been to me musically.

“The album is essential listening for anyone interested in English traditional music, and not only for the wealth of lovely tunes, but also for that special feeling of music-making bringing people together socially. “Folk” music always seems to me to be something from a book or manuscript, whereas in “traditional” music we can connect with previous generations in a much more personal way; their individual fingerprints are all over it, in a way which can be felt in recordings such as these. And wouldn’t Walter Bulwer be absolutely amazed if he dropped into a pub these days and found hordes of people playing the polkas he led for this recording? Rumour has it that they nearly didn’t make the edit, as sixty years ago they were felt to be a bit too modern in style!” (23)

On a personal note, of the bands promoting Norfolk’s traditional music I’ve been involved with, the 2020 CD Foundlings by the band Hushwing was an attempt to bring together and record a selection of obscure tunes from Norfolk, very much in the spirit of the original record, as mentioned in the booklet notes: “Our model has been the group of musicians gathered together by Mervyn Plunkett and Reg Hall for the recordings by Bill Leader made in 1962 at the home of Walter and Daisy Bulwer in Shipdham” (24) and perhaps the spirit of “these were not spotless performances in terms of recording studio multi-take perfection…these were lively, ready-for-dancing performances” (25) was very much present with our recording and the finished result. Certainly the original record was a great influence on proceedings in every respect.

So, it is fitting that the original Record No 1 of sixty years ago continues with its iconic status amongst musicians who are aficionados and proponents of English country dance music with a very traditional basis. Fitting too that the expanded CD version of English Country Music is still readily available, to continue to delight, inform and inspire. In fact, the CD version, vastly expanded in tracks as it is, gives a much wider sampling of what made these sessions so magical, providing more music by the older generation musicians in the sessions. In both versions, the album continues to play its part to ensure that the vernacular, traditional music of this area continues to thrive, albeit under different social circumstances from those when the Bulwers and Billy Cooper were active community musicians. To quote Lily Codling, the last surviving member of the Bulwers’ Time and Rhythm band of earlier in the Twentieth Century, about Walter’s probable reaction, “What would he feel now, he knew this all come about?” (26)

Chris Holderness November 2025

Notes:

- English Country Music Topic 12T296

- TSCD607

- Scan Tester’s music was released extensively on the Topic 2 LP set: I

Never Played to Many Posh Dances – 2-12T455/6 – in 1990. A

slightly expanded CD version – TSCD581D – was released in 2009. - An EP featuring three of these singers was released on Collector

Records in 1961: 4 Sussex Singers – JEB 7. It included songs by Jim

Wilson, Pop Maynard, George Spicer and Jean Hopkins. - Reg Hall: I Never Played to Many Posh Dances: Scan Tester, Sussex

Musician 1887-1972 Musical Traditions supplement no. 2 (1990)

p. 60. The LP set (Note 3, above) was released to accompany this

publication. - Booklet notes by Reg Hall for the CD version of English Country

Music p. 2 - Ibid. Hall ECM p.3

- Ibid. Hall ECM p.4

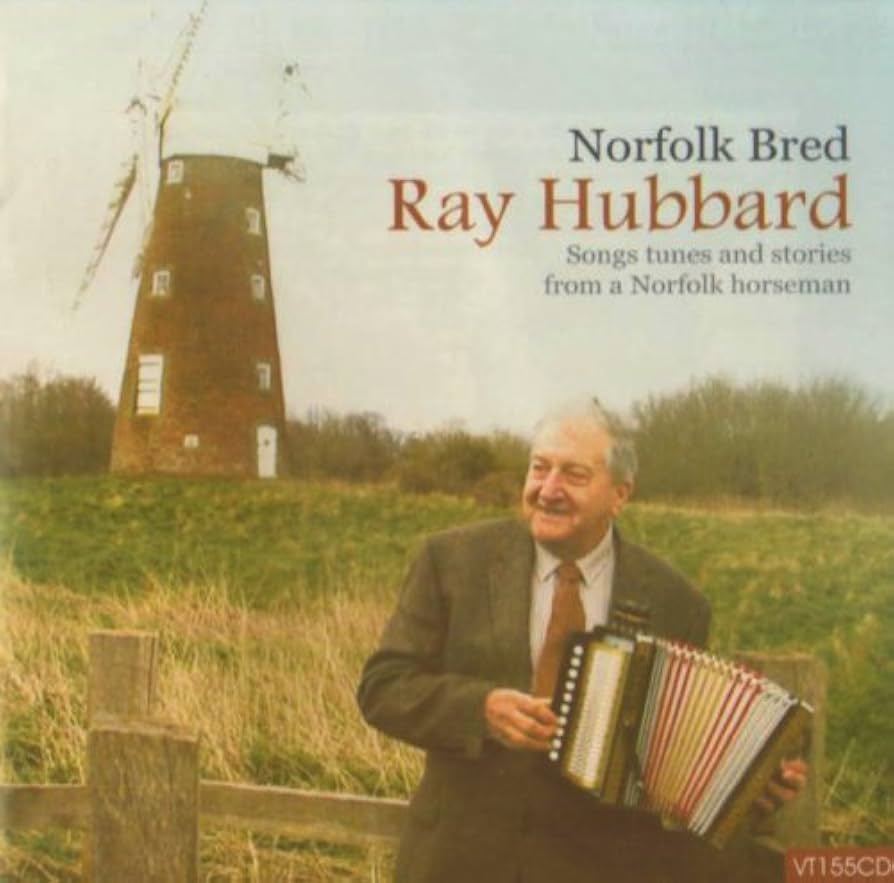

- Heel and Toe Veteran VT150CD (2005). The tracks are: Yarmouth /

Sailor’s / Yarmouth Hornpipes; Whistling Rufus and Unidentified

Polka (Cromarty Polka March). Walter and Daisy Bulwer also play an

Unidentified Jig (Warbler’s Serenade) and Billy Cooper plays Dulcie

Bell. - Ibid. Hall ECM p. 5 & 6

- Ibid. Hall ECM p. 7

- Ibid. Hall ECM p.8

- Rod Stradling, in his review of the Hushwing CD Foundlings:

Musical Traditions 28.03.20 - Ibid. Hall ECM p. 10

- The track was not included on the CD version.

- Ibid. Hall ECM p. 11

- 12T296, as above.

- Now known popularly as Walter Bulwer’s Polka No 1 and Walter

Bulwer’s Polka No 2. The first is track 3 on side 1. The second wasn’t

included on the original LP but did appear on Topic’s LP Boscastle

Breakdown: Southern English Country Music: 12T240, 1974, and is

included in the CD edition. (The other Untitled Polka on the original

LP – side 1, track 7 – is a version of the Helston Furry Dance.) - Ibid. Hall ECM p. 11

- Rod Stradling, correspondence: 01.09.25. The review alluded to

was published in Musical Traditions on 10.10.00. - 12T196, as above. The first reissue in 1976 was housed in a

gatefold sleeve. Later pressings were presented in a single sleeve. - In particular Walter’s No 2 Polka, which has three parts, the third

of which is rarely played, unfortunately. He played the parts in F, C

and B flat, again not as played usually today. - Katie Howson, correspondence: 19.11.25.

- From the booklet notes by Alan Helsdon for the Hushwing

Foundlings CD (Quanting QCD 20.03) 2020, p. 2. - Ibid. Helsdon p. 2.

- Chris Holderness: Walter and Daisy Bulwer: Recollections of the

Shipdham musicians by members of the community published in

Musical Traditions: MT185, 25.08.06. This quote was used to

conclude that article, but seems equally apposite here. A similar

article with details of Billy Cooper’s life can be found at the same site:

Billy Cooper: the Hingham dulcimer player remembered by his family:

MT211, 16.07.07.

Appendix

The tracks on Record No 1 (and the Topic LP reissue) are:

Side 1: 01: The Bluebell Polka 02: Waltzes: The Foggy Dew / The Young

Sailor Cut Down in His Prime 03: Untitled Polka 04: Jig: Off She Goes

05: Polka: Red Wing 06: Waltzes: Believe Me If Those Endearing Young

Charms / Johnny’s So Long at the Fair 07: Untitled Polka (Helston Furry

Dance)

Side 2: 01: Polkas: Jenny Lind / The Girl I Left Behind Me 02: Peggy Wood

/ When There Isn’t a Girl About 03: Schottisches: Washing Day / Old Mrs

Huddledee / The Cat’s Got the Measles 04: The Waltz Vienna

05: Hornpipes: The Four Hand Reel / Soldier’s Joy 06: Polka: Shepherd’s

Hey