By Jim Carroll and Pat Mackenzie

“Popular tradition, however, does not mean popular origin. In the case of our ballad, the underlying folklore is Irish de facto, but not de-jure: the ballad is of Oriental and literary origin, and has sunk to the level of the folk which has the keeping of folklore. To put it in a single phrase, memory not invention is the function of the folk”. [our italics]

Note by Phillips Barry to ‘Lake of Col Finn’, in the Helen Hartness Flanders collection, New Green Mountain Songster, Yale University Press, 1939

The writer of the above note, American Phillips Barry, was regarded as an eminent folk song scholar in the early part of the 20th century. Aside from a distaste for the phrase ‘sunk to the level of the folk’, it seems somewhat dismissive of the talents of those who gave the collector for whom he was writing, many wonderful examples of the oral song tradition. Of course, memory is of utmost importance to the singer but the act of creation involved in singing also embraces ‘invention’, a process developed from thought and imagination. To be fair to Barry, his statement is at variance with a number of comments that he makes in the Foreword to the above collection. There he writes of the folk singer’s prerogative to be also folk composer, to recreate textually and musically a song he has learned. It is this latter assertion that has been our experience over the thirty years during which we have been talking to and recording singers, and we would like to draw on our work with the English singer, Walter Pardon, as illustration. All quoted passages are taken from interviews recorded between 1975 and 1993.

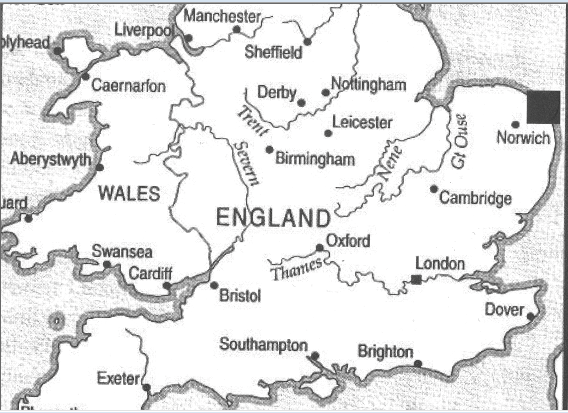

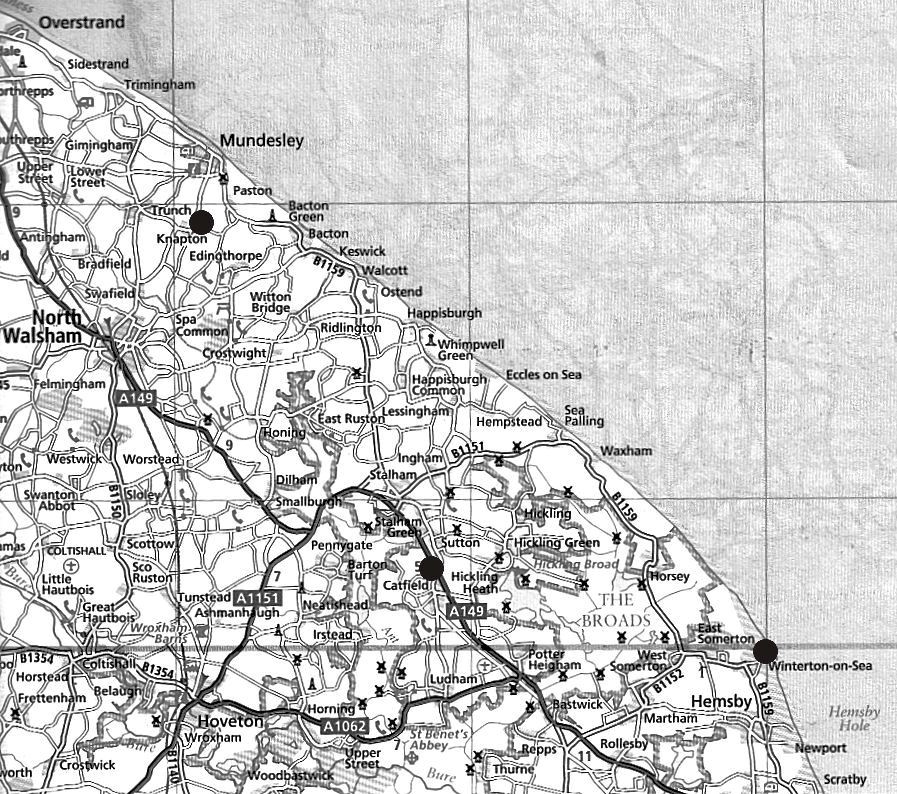

East Anglia in South East England has proved a fertile area for traditional song, probably due in part to its relative isolation [see map below]. Norfolk, in particular, produced three fine singers in the 20th century: farmworker Harry Cox from Catfield; Sam Larner, a fisherman from Winterton; and lastly, Walter Pardon of Knapton, a carpenter from a farming background, each living within twenty miles of each other. In the earlier years of the 20th century, collectors like Ralph Vaughan Williams and E.J. Moeran were finding the county a rich source of traditional song: particularly noteworthy was Moeran’s work in the l920s with Harry Cox. In the 1950s, the BBC’s mopping up campaign was still unearthing singers with a wealth of material despite the fact that, by that time, the singing tradition in England had entered a steep decline and, indeed, had almost died out, leaving us with a handful of traditional singers and a somewhat larger number of what Ewan MacColl aptly described as song carriers’: people who had not necessarily been part of the singing tradition but, for one reason or another, had clung on to some of the old songs and music. Although lucky enough to catch Harry Cox and Sam Larner in the flesh just once, we were able to spend twenty years with Walter Pardon, the youngest of the trio, from 1975 until his death in 1995

Walter was born in 1914 into a family of mainly agricultural workers employed on local farms and also as gardeners and groundsmen at local golf links. Knapton is a small rural village, a couple of miles from the sea at Mundesley and the same distance from the market town of North Walsham; it has no pub and the single small shop closed years ago. When Walter was growing up, the roads were unmade which meant outside influences were very few. Walter was born and lived all his life in the same house that his mother and her siblings were all born in and into which Walter’s maternal grandparents moved when they were first married, probably about the mid-19th century. His mother’s father was apparently the main source of the family songs and played clarinet in the church gallery, in the choir, and was a bellringer. His maternal great grandfather had moved to the village from North Walsham in about 1820. The earliest Walter knew of his father’s family connection with Knapton was his great, great grandfather’s grave, dated 1851.

Walter was an only child and so became the focus of attention, not only of his parents but also of the two bachelor uncles [his mother’s brothers, Walter and Billy] who lived with them. Walter appeared to have had a happy childhood but times were hard. As a boy, he, along with other children, helped on the land: pulling beet, pitching hay up on to the stacks, etc. At that time, the children’s summer holidays were determined by the dates of the harvest; the farmers told the schools when they were going to start so that the holidays could coincide. They worked from dawn to dusk six days a week. Walter was told of earlier times.

‘Years back the children, when they used to hollow out the turnips and mangles, instead of cutting them out right clean like they done when I remember, they, little children, crawl in between the rows and pull them out with their fingers’.

He related how his Uncle Billy was sent off to work alone on one occasion:

‘There’s a long loke [boreen], a mile long and he was sent down the loke to work alone and he said to one of the men, ‘How shall I know the time, no watch’ So the man say, ‘When you can see two stars with one eye, leave off work’.So Billy could see two, come up into the yard and John Blanchflower [the farmer] was there; he said, ‘You left off early Billy’. Billy said, ‘I was told when I could see two stars with one eye I could leave off’. And the old man look up and he say, ‘I can see more than two so you’ve got a right to stop work’. So that’s how he got out of that one all right’.

Walter spoke of his great grandfather, unusually named Brown Pardon, who worked for a farmer in Knapton and they quarrelled:

‘I think he swore at the old man. Anyone who answered back, you see, that was instant dismissal in them days then, this would be, I should think, in the early 1850s or even 1840s. He was given instant dismissal and no-one would employ him. My grandfather and his three sisters, he had to keep them and their mother. He’d got no money so he went to Yarmouth and went to sea, like Sam Larner did, you know, this trawling. My grandfather and his sisters and the mother had to go into Gimmingham Workhouse while he was away at sea, ’cause no-one would employ him. There’s a man told me that when his mother was a little girl, they all come past the house crying to think they had to go in the workhouse; she cried to see them cry. But father said my grandfather told him he liked it in the workhouse, it was warm and he was fed. Well, they’d have starved, workhouse or starve, so they went in there until he could come home with some money’.

Walter was apprenticed as a carpenter in the neighbouring village of Paston when he left school at 14 and he worked mainly locally, probably within a radius of 20 miles, cycling to work each day. He never lived away from Knapton except for his four years War Service when he was employed as a carpenter on various Army camps about the country.

The Gees, his mother’s family, were musical: singers and instrumentalists. In the past, they had played fiddles, concertinas, clarinets and accordeons but Walter had only heard his Uncle Walter who played melodeon and Jews Harp. Walter learnt songs from his family: his mother, his Aunt Alice and, principally, his Uncle Billy. Billy, who was born in 1863, had a great number of songs from his father, Tom Gee, who was well known as a singer with a very large repertoire. Walter remembered, as a child, sitting on Billy’s knee and absorbing the songs and tunes. He was about seven years old when he learnt his first complete song,

The Poacher’s Fate (Roud 793; Laws L14)

Who love to drink strong ale that’s brown

And pull aloft a pheasant down

With powder shot and gun

I and five more a-poaching went

To kill some game was our intent

Our money gone and all was spent

We’d nothing else to try

The moon shone bright

Not a cloud in sight

The keeper heard us fire a gun

And to the spot did quickly run

He swore before the rising sun

That one of us must die

‘Twas the bravest youth among the lot

‘Twas his misfortune to get shot

In memory he’ll ne’er be forgot

By all his friends below

In memory he ever shall be blest

He rose again to stand the test

Whilst down upon his gallant breast

The crimson blood did flow

For help he cried But was denied

It was the wound the keeper gave

No mortal man his life could save

He Now lies sleeping in the grave

Until the judgment day

That youth he fell upon the ground

Within his breast a mortal wound

Whilst from the woods a gun did sound

That took his life away

The murderous man that did him kill

All on the ground his blood did spill

Shall wander far against his will

And find no resting place

Destructive things His conscience stings

He must wander through this world forlorn

And always feel the smarting thorn

That pointed out with finger’s scorn

And die in sad disgrace

To prison then we all were sent

We called for aid But none was lent

Our enemies they were full bent

That there we should remain

But fickle fortune on us shine

And unto us did change her mind

With heart felt thanks for liberty

We were let out again

No more locked up in those midnight cells

To hear the turnkeys ring the bells

Those cruckling doors I bid farewell

The rattling of the chain

The family was constantly acquiring songs: from neighbours, gramophone records, etc., and Walter knew several Irish songs from workers who had travelled to the area to work on the land [we found several Irish names in the area, e.g. Murphy and Cahill]. The singing was done at Harvest Frolics, the celebrations after the harvest, which died out while Walter was young, and at Christmas parties. Apparently so many people came to the cottage then that they had to have meals in two sittings.

I can remember going, it’s finished now, the old beer stalls at North Walsham. I think the man is dead now, Arthur Harvey. I don’t know how many years back, I got four little bottles of nips I think they were, put in a bag. He says, ‘Is that all you want,’ I says, ‘Yes, that’ll be enough for me’. ‘My word’, he said, ‘It’s a lot of difference now than what used to be carted in to your house. There used to be a lot come’. I say, ‘Yes, very near twenty’. He say, ‘I carted more beer to that house ready for Christmas night than any house I went to and I went miles!’.

There would be conversation, music, singing and dancing at these parties but always perfect quiet for the songs. The living room had an exposed beam running across the ceiling called the baulk and the shout would go up, Our side of the baulk after someone had sung from one side of the room and they would take turns across the room. They each had their own particular songs for these occasions. Apparently no-one wanted The Dark Eyed Sailor so that was Walter’s song, or sometimes When The Fields Were White With Daisies. They all knew the tunes but everybody was very protective of their own songs and did not want others to learn them. As the favourite youngster, Walter was the only one to whom Billy Gee would give his songs but none of his contemporaries wanted them anyway; they would only learn new songs as they came out.

There used to be Christmas night and the Harvest Frolics, yes. Well they sung the songs as they learnt as new. The ages stretched so much, you see, from the oldest down to the youngest and there was years difference, you very near knew when they were born by the songs, you see. They’d be the folk songs that went back probably to the eighteenth century, early nineteenth; then when the younger ones come along, songs would be sung what they learned perhaps in the eighteen or nineteen hundreds, up to early perhaps nineteen twenty. So they all learnt them as new, as they come out in their time. And there was only me learnt the old ones, you see, what had gone back, what grandfather sung.

The Harvest Frolics finished when I was a boy, anyhow. Then that gradually died as the old people kept dying; then the old Christmas parties finished altogether, so there was no more left to carry it on and no-one left but me who knew the songs.

There was no pub singing in Walter’s time but he knew that there had been in the past which Billy had taken part in from the age of about seventeen [1880], at the Mitre Tavern in North Walsham in particular.

They had a singing room there and that was where they used to assemble with accordeons and flutes and fiddles and singing and step dancing, all that sort of thing. And he used to go up Thursday nights, walk up, that’s market day in North Walsham. That was the night they held the singing.

Walter heard Billy sing only once in a pub: after an Agricultural Workers’ Union meeting at the Crown in Trunch, the next village. Walter was very proud of his family’s association with the early Agricultural Union movement. When George Edwards restarted the Agricultural Workers Union in Norfolk in 1907, the first one started by Joseph Arch in the late 19th century having folded, Walter’s father Tom had the second Union card issued, Nos.1 and 3 going to men from nearby villages. Forty years later, all three men were awarded silver medals for their services to the Union. Walter learnt a number of songs, parodies and rhymes connected with the Union; for example:

Old Man’s Advice (Roud 1482)

(To the tune of Grandfather’s Clock)

My grandfather worked when he was very young

And his parents felt grieved that he should,

To be forced in the fields to scare away the crows

To earn himself a bit of food.

The days they were long and his wages were but small,

And to do his best he always tried,

But times are better for us all

Since the old man died.

For the union is started, unite, unite,

Cheer up faint hearted, unite, unite,

The work’s begun, never to stop again

Since the old man died.

My grandfather said in the noontide of life,

Poverty was a grief and a curse,

For it brought to his home sorrow, discord and strife

And kept him poor with empty purse.

So he took a bold stand and joined the union band,

To help his fellow men he tried,

A union man he vowed he’d stand

Till the day he died.

For the union…

My grandfather’s dead, as we gathered round his bed,

These last words to us he did say:

Don’t let your union drop nor the agitation stop,

Or else you’ll soon rue the day.

Get united to a man, for it is your only plan,

Make the union your care and your pride,

Help on reform in every way you can,

Then the old man died.

For the union…

Influenced by his family’s love of song and music, Walter developed a deep interest in the songs he said he supposed he’d inherited it. After his Uncle Billy died in 1942, he began writing down his family’s songs on scraps of paper and in exercise books; one notebook was dated 1948. Including fragments, we recorded over 200 songs from him, with a solid base of some 100 complete songs, largely traditional.

It is interesting to study Walter’s tunes which are often similar to familiar versions but subtly different. It is difficult to say that this is exactly how he learnt them, although he thought so. During the long period of not hearing them, at least 20 years, he kept the songs alive for himself by playing the tunes on the melodeon. Did they perhaps get changed then? Were certain phrases easier for him to play on the melodeon? Or was it simply his own creativity, that he preferred certain musical phrases to others? We’ll never know, of course, but certainly Walter’s tunes are a little different to standard versions and very distinctive.

Walter was aided in putting together songs which he had heard but never sung by his prodigious memory. He was able to describe local lore and events not only from his own experience but those which had been recounted to him by his elders. He could recall long vanished field names, local words and names of animals, farm implements, etc. We gave him an exercise book once and asked him, if he had time, would he write down some of the sayings, proverbs, stories, dialect words, etc. Shortly after, he had filled every page completely with close writing; bought two more books and filled them in the same way.

Aware that Walter had been putting together the family repertoire, his cousin’s nephew, Roger Dixon, who had also been interested in the songs from a boy, endeavoured to persuade him to put some on tape.

Eventually, having bought a tape recorder, Walter set about it and later described his efforts at recording himself:

I used to think I could manage to sing the old Rambling Blade; I put it on and it sound so blooming horrible I wiped it right out; oh, that did sound dreadful. I don’t think that was as bad, perhaps, as I thought it was but that was a long while, trying different things until I thought that was better as I kept hearing it, you see. And I know that was about October, 1972, when I started it. Oh, I don’t know, it took about up to Christmas time to fill one side; I used to forget there was verses in the songs, you see, I used to keep wiping it out and putting them on again. That took a long time to get them up into the pitch I could sing them in, not having sung the things. Well, I got one side done somewhere from the October up to the Christmas1972 this was. And I know when it come over to the following New Year, I was in here one Saturday night and that was bitterly cold; oh, that was a wind frost, wind coming everywhere. I was that cold, I had a big fire going one side and that little stove the other. So I thought then I’d do some more taping so I got warmed up; I had a strong dose of rum and milk, and I had another one. And so I got the tape recorder going, I can remember well enough, that was Caroline And Her Young Sailor, and when I finished it was the best I ever did do. Well, I found out I drank more than I should, I had to keep right still, that was true. In fact, I was drunk. and then of course I went to bed; I never did have any more. And the next morning when I got up and tried it I knew I was, how that was coming out with all the words all slurred, so I wiped it all out. Well, I found then as I kept going, that it wouldn’t pay to drink anything. Anyhow, eventually that was filled up in the March; that was March 1973.

Roger Dixon passed these tapes to Revival singer Peter Bellamy, a former pupil of his and, recognising Walter for the superb singer that he was, Peter passed them on to record producer, Bill Leader, who went to Knapton and recorded material for two albums: A Proper Sort And Our Side Of The Baulk.

This opened up a whole new world that Walter had not known existed: first at the Norwich Festival and later at folk song clubs throughout the country.

I had a vague idea they had folk clubs of some description: all these doctors, solicitors etcetera, would go and sing in someone’s big house. I never realised, you see, working people done that, never knew a single thing about itâ€.

From the outset, Walter’s approach to his new-found celebrity was professional: To him, performing was a job to be done properly and for which he prepared carefully, so that he did not forget words or pitch wrongly and he only ever drank shandies slowly. He gave a lot of thought to his singing and always stressed the importance of singing naturally, as spoken. He had his own positive ideas and he became very disturbed at the way in which some audiences would completely ignore, for instance, the speed at which he was singing and would draw out the choruses painfully slowly so that he found himself way ahead and trying to adapt to the audience. He considered, quite rightly, that this was very discourteous, if nothing else, and he dropped one song from his working repertoire for that reason. He told us that his Uncle Billy, his greatest influence, sang quite steady and straightforwardly and, although Walter did not think he sang as fast, he must have been affected by Billy’s style to a degree; he always resisted the temptation to drag out ballads. Referring to pacing a song, he said you had to have the right strook; perhaps Norfolk dialect for stroke but he spelt it for us: STROOK.

It is perhaps surprising that the collectors working in Norfolk missed a family of singers such as the Gees but it was certainly quite phenomenal that, out of the blue, appeared a singer of such ability with such a large, rich and varied repertoire and such splendid tunes. The ease and conviction with which he handled his material [classic ballads, bawdy songs, Victorian parlour ballads, Union or Music Hall songs] was striking as was the informed, intelligent and emotional response to them, particularly the depth of his involvement.

It is revealing to note his choices when asked to list six songs for a performance:

The Pretty Ploughboy would be one, that’s one; The Rambling Blade would be two, Van Dieman’s LAND three, Let The Wind Blow High Or Low, that’d be four, Broomfield Hill, that’s five, Trees They Do Grow High, six, that’d be six.

These are all from the classical traditional repertoire, including one Child ballad, of which he had several. Broomfield Hill was certainly one of his favourites:

Broomfield Hill (Roud 34; Child 43;)

‘A wager, a wager with you, pretty maid,

My one hundred pounds to your ten,

That a maid you shall go into yonder green broom,

But a maid you shall never return.,

‘A wager, a wager with you, kind sir,

Your one hundred pounds to my ten,

That a maid I shall go into yonder green broom,

And a maid I shall boldly return.’

And when she arrived down in yonder green broom

She found her love fast asleep,

Dressed in fine silken hose with a new suit of clothes

And a bunch of green broom at his feet.

Then nine times did she go to the soles of his feet,

Nine times to the crown of his head,

And nine times she kissed his cherry red lips,

As he lay on his green mossy bed.

Then she took a gold ring from off of her hand

And placed it on his right thumb,

And that was to let her true love to know

That his lady had been there and gone.

Then nine times did she go to the crown of his head,

Nine times to the soles of his feet,

And nine times she kissed his cherry red lips

As he lay on the ground, fast asleep.

And when he awoke from out of his sleep

‘Twas then that he counted the cost,

For he knew that his true love had been there and gone

And he thought of the wager he had lost.

He called three times for his horse and his man,

The horse that he bought so dear;

Saying, “Why didn’t you wake me out of my sleep

When my lady, my true love, was here.”

Oh master, I called unto you three times,

And three times I blew on my horn,

But I could not wake you out of your sleep

Til your lady, your true love, had gone.

Farewell and adieu to her loved one in gloom,

Farewell to the birds on Broomfield Hill.

A maid she did go into yonder green broom

And a maid she remains forever still.

Yeah, that sounds an old tune, don’t it? Nine has gone in, the witches number.

Walter maintained that a good imagination was essential to the singer and felt that his singing had matured in this respect since his first public performances:

‘…put more expression in probably; I think so. Well, you take these, what we call the old type…the old folk song, they’re not like the music hall song, are they, or a stage song? There’s a lot of difference in them… it all depend what and how you’re singing. Some of them go to nice lively, quick tunes, and others are…well, if there’s a sad old song you don’t go through that very quick Up To The Rigs is the opposite way about.

I mean, we must put expression in, you can’t sing them all alike. Well, most of the stage songs you could, if you understand what I mean. According to what the song is, you put the expression in or that’s not worth hearing; well, that’s what I think anyhow’.

Walter’s always thoughtful evaluation of songs was interesting. He said that, if he performed before a big crowd, he liked to sing The Pretty Ploughboy: because it ends happily; so many ended with being transported or shot or something going wrong; like Van Dieman’s Land – a sad old song. He also said it was a long old song but it was a long old journey an indication of the strength of his sympathy and identification with the story.

J. C. When you’re singing in a club or at a festival, what do you see when you’re singing?

W. P. Actually what I’m singing about; like reading a book. You can always imagine you can see what’s happening there; you might as well not read it.

P. M. How do you see it, as a moving thing or as a..?

W. P. That’s right. The pretty ploughboy was always ploughing in the fields over there; that’s where that was supposed to be.

J. C. How about Van Dieman’s Land?

W. P. Well, that’s sort of imagination what that was really like; I mean, Warwickshire; going across, you know, to Australia; seeing them chained to a harrow and plough and that sort of thing; chained hand-to-hand, all that. You must have imagination to see, I think so.

That’s the same as reading a book: you must have imagination to see where that is, I think so; well I do anyhow.

P. M. But you never shut your eyes when you’re singing, do you?

W. P. No, no.

P. M. So if you haven’t got a microphone to concentrate on; if you’re singing in front of an audience, where do you look?

W. P. Down my nose, like that!

Walter’s ability to differentiate between the various types of song in his repertoire belied the popular perception of the traditional singer as being totally non-discriminatory. This is how he explained how he judged the age of his tunes with the aid of his accordeon:

Well yes, because there’s a difference in the types of the music, that’s another point. You can tell Van Dieman’s Land is fairly old by the sound, the music, and Irish Molly and Marble Arch is shortened up; they shortened them in the Victorian times. And so they did more so in the Edwardian times. Some songs then, you’d hardly start before you’d finish, you see; you’d only a four line verse, two verses and a four line chorus and that’d finish. You’d get that done in half a minute; and the music wasn’t as good. Yes, the style has altered. You can nearly tell by The Broomfield Hill, that’s an old tune; The Trees They Do Grow High, you can tell, and Generals All.

Nine times out of ten, I can get an old fashioned ten keyed accordion, German tuned, you can nearly tell what is an old song. Of course, that doesn’t matter what modern songs there is, the bellows always close when that finish, like that. And you go right back to the beginning of the nineteenth and eighteenth [century], they finish this way, pulled out, look. You take notice how Generals All, that got an old style of finishing, so have The Trees They Do Grow High, so have The Gallant Sea Fight, in other words, A Ship To Old England Came, that is the title, The Gallant Sea Fight. You can tell they’re old by the drawn out note at the finish. Well, a lot of them you’ll find, what date back years and years, there’s a difference in the style of writing the music. Like up into Victorian times, you’ve got Old Brown’s Daughter; well that style started altering, they started shortening the songs up, everything shortened up, faster and quicker, and the more new they get, the more faster they get, the styles alter. I think you’ll find if you check on that, that’s right.

Walter had a quiet sense of humour, which was often reflected in his choice of songs, such as, The Steam Arm, Dark Arches, The Dandy Man and The Cunning Cobbler; this last he described as “Chaucerianâ€.

He also had quite a few non-traditional songs that he had heard and learnt, but he sang them in the same traditional style as his other songs. He always maintained a quiet, still stance; he had no affectations and never imitated music hall mannerisms. He had only fragments and tunes of several songs so he put them together from books and broadsheets; he virtually reconstructed one song to fit his tune and chorus. He said he had to cut the words to fit his tune; he liked the words to go out with the nice flow of the tune. The only song which, to our knowledge, was completely new to him was, in fact, a poem by Thomas Hardy. He made a tune for The Trampwoman’s Tragedy, which is written in ballad form, but he never learnt it or sung it in public.

Walter had always read a lot and probably even more so after his father died in 1957 leaving him living alone for nearly 40 years. Hardy, Dickens, H.E. Bates, Zane Grey – he had quite catholic tastes, probably with a preference for the Victorian writers but mainly just for a good story which he remembered with amazing clarity, often quoting from books that he had not read for perhaps 20 years or more.

Walter was proud of his family’s songs and he considered it very important that they were sung well in public. Having lived a fairly sheltered life, not having seen many live performances, he found himself, at the age of 59, suddenly propelled into a strange, new world which he took calmly and modestly in his stride. However, because of his intense involvement with his songs, he did find performance quite draining and, at the age of 75, he felt that it was difficult for him to maintain the high standards he had set himself and so decided to stop singing in public.

We first met Walter in 1975 and became very close over the following twenty years. He was a wonderful companion, a real delight, a very humourous, gentle, kind man, incredibly generous with his material and his time. The first time we called on him as complete strangers, we had only been chatting a short while when he asked, Have you a tape recorder with you?

Walter put great store on passing the songs on; on several occasions he said “They’re not my songs, they’re everybodys. This, to a degree, went against what had happened in the past, especially within his own family, where the singers had jealously guarded their songs, even to the extent of altering words or omitting verses if they thought there was somebody present trying to learn them. He was insistent that it was generally recognised that, at home, some songs belonged to certain singers and that nobody else would sing them in the presence of the owner. However, throughout his life he persisted with his belief in the common ownership of songs:

I saw a chap at Happisburgh this summertime, he said he knew songs, he said, “I always refuse to let anyone have them. Once you let someone else have them they aren’t yours”. Well, I say, that is true, but I say, when you die you take all the knowledge of the songs with you, so someone might as well have the benefit after you are dead.

Walter Pardon Discography

A Proper Sort Leader LED 2063 Yorkshire 1975

Our Side Of The Baulk Leader LED 2111 Yorkshire 1977

An English Folk Music Anthology Folkways FE 83553 New York 1981

A Country Life Topic 12TS392 London 1982

Bright Golden Store Home Made Music HMM LP 301 London 1984

Up To The Rigs Peoples Stage Tapes 11 Totnes, Devon 1987

The Horkey Load [Nos. 1 and 2] Veteran Tapes VT108 & VT 109 Suffolk 1988

Hidden English Topic TSCD600 London 1996

Voice Of The People Topic TSCD651 to 670 London 1998

[Nos. 1, 2, 4, 6, 10, 14, 15, 17, 18]

A Century Of Song E.F.D.S.S. EFDSSCD02 London 1998

A World Without Horses Topic TSCD514 London 2000

Put A Bit Of Powder On It Father Musical Traditions MTCD 305-6 Gloucestershire 2000

Walter Pardon’s Repertoire

All Among The Barley

All For Me Grog

All Jolly Fellows (f rag)

All The Little Chickens In The Garden

As I Wandered By The Brookside

Balaclava

Bald Headed End Of The Broom

Banks of Allan Water

Banks of The Clyde

Bells Are Ringing For Sarah

Best Old Wife In The World

Black Eyed Susan

Black Velvet Band

Blow The Winds I O

Bluebell

Boat Is Going Over

Bold Fisherman

Bold Princess Royal

Bonny Bunch of Roses

Boys in Navy Blue

Bright Golden Store

British Man Of War

Broomfield Hill

Burningham Boys

Bush of Australia

Butter And Cheese And All

Caroline And Her Young Sailor Bold

Carrion Crow

Cock-a-doodle-doo

Coltishall School Treat

Come And See The Kaiser (Harland Road)

Come Little Leaves

Come To Me In Canada

Country Life

Cuckoo

Cunning Cobbler

Cupid The Ploughboy

Dandy Man

Dark Arches

Dark Eyed Sailor

Darling Dinah Kitty Anna Maria

Derby Ram

Deserter

Devil and the Farmer’s Wife

Dinah Kitty Anna Maria

Dolly Varden Hat

Down By The Abbey Ruins

Faithful Sailor Boy

Farmer’s Boy

Farmyard Song

Female Drummer

Footprints in the Snow

Game Of Dominoes

Generals All

Genevive

Give My Love To Nancy

Goodbye King (election parody to Dolly Grey)

Gooseberry Tree

Gorgonzola Cheese

Green Bushes

Green Grows The Laurels

Handsome Cabin Boy

Hanging on the Old Barbed Wire

Has Anybody Seen Our Cat

Help One Another Boys

Hockey Tar Tarry Tee

Hold The Fort

Home Boys Home

Hungry Army

Huntsman

Husband Taming

I Don’t Care If There’s A Girl There

I Wish I Wish

I Wish They’d Do It Now

I’ll Hang My Harp on a Willow Tree

I’z Yorkshire Though In London

If I Were A Blackbird

If I Were A Policeman

If Those Lips Could Only Speak

If Those Lips Could Only Speak (parody)

I’ll Be All smiles Tonight

I’ll Come Back To you My Sweetheart

I’ll Have No Union (Farmer’s boy Parody)

I’ll Walk Beside You

I’m Bound To Emigrate To New Zealand

I’m Yorkshire Though in London

In Our Backyard Last Night

In The Shade of The Old Apple Tree

Irish Girl

Irish Molly O

It’s For The Money

It’s Hard to Say Goodbye To Your Own Native Land

Jack Hall

Jack Tar On Shore

Jackie Boy

John Barleycorn

John Reilly

Jolly Waggoner

Jones’ Ale

Just Down The Lane

Kitty Come Come

Kitty Wells

Lawyer

Little Ball of Yarn

Long A’growing

Lord Lovell

Loss of The Ramilles

Maid of Australia

Maid of the Mill

Marble Arch

Men of Merry Merry England

Mermaid

Miller’s Three Sons

Miner’s Dream of Home

Miner’s Return

Mistletoe Bough

More Trouble In My native Land

Mother Machree

My Little Blue Apron To Fill (The Gleaner)

My Old master Told Me

Nancy Fancied a Soldier

Naughty Jemima Brown

Not For Joe

Oak And The Ash

Oh Joe Do Let Me Go

Oh Joe The Boat is Going Over

Old Armchair

Old Brown’s Daughter

Old Kentucky Home

Old Miser

Old Mother Pittle Pots

Old Rustic Bridge By The Mill

Old Woman of Yorkshire

One Cold Morning In December

Parson And The Clerk

Parson Brown

Peggy Band (John Clare’s version with Walter’s tune)

Peggy Band (trad. version)

Poacher’s Fate

Polly Vaughan

Poor Little Joe

Poor Roger Is Dead

Poor Smuggler’s Boy

Pretty Ploughboy

Put A Bit of Powder On It Father

Raggle Taggle Gypsies

Rakish Young Fellow

Rambling Blade

Ratcliff Highway

Ring The Bell Watchman

Rise Sally Walker

Rosin The Beau

Sailor Cut Down In His Prime

Saucy Sailor Boy

Seventeen Come Sunday

Shamrock Rose And Thistle

She Stood In A Working Man’s Dwelling

Ship Sailed Away From Old England

Ship That Never Returned

Ship To Old England Came

Silver Threads Among The Gold

Skipper and His Boy

Slave Driving Farmers

So I Will

Soldier Boy (Butcher Boy)

Somebody Had To fetch The Flag

Sons Of Labour

Spanish Cavalier

Stars and Stripes and John Bull Forever

Steam Arm

Stick To Your Mother Son

Strawberry Fair

Susan The Pride Of Kildare

Suvlah Bay

Sweet Belle Mahone

Ten Thousand Miles Away

That’s How You Get Served When You’re Old

There’s a Long-long Trail

They All Do It

They Don’t Grow On Tops of Trees

Thirty Nine/Forty Five Star

Thornaby Woods

Topman And The Afterguard

Trampwoman’s Tragedy

Trees They Do Grow High

Turning The Mangle

Two Jolly Butchers

Two Little Girls in Blue

Two Lovely Black Eyes

Up To The Rigs

Van Dieman’s Land

Wake Up John

Wanderer

Wearing Of The Green

We’re All Sawing

We’ve Both been Here Before

Wheel Your Perambulator

When Father Joined The Territorials

When London’s Asleep

When The Cocks begin To Crow

When The Fields Are White With Daisies

When You Wake Up In The Morning

While Shepherds Watched

Will You Come Back To Bombay

Wind Blows High

Wing Wang Waddles

Woman’s Work Is Never Done

Won’t You Come To Me In Canada

Woodman Spare That Tree

Would You Like To Know How Bread Is Made

Wreck of The Lifeboat

Write Me A Letter From Home

You Wore A Tunic

This article was written for publication in The Old Kilfarboy Society, 2007. It was included in Dear far-voiced veteran: essays in honour of Tom Munnelly (ed Anne Clune).

In July 2021 Jim Carroll and Pat Mackenzie kindly agreed to pass digitised copies of their work on collecting in Norfolk to EATMT for their conservation and preservation and we thank them for the permission to include this article on the Trust webiste.

July 2021