An appraisal of the Norfolk singer in “Ethnic” magazine, 1959

“There’s people making money out of these hare old songs, but it’s not us.” – Harry Cox

In the late 1950s, as the post-war revival of interest in traditional music and song was

gaining momentum, there were considerably fewer opportunities or forums available for those wishing to read, write or find out about the subject, than there are today. One

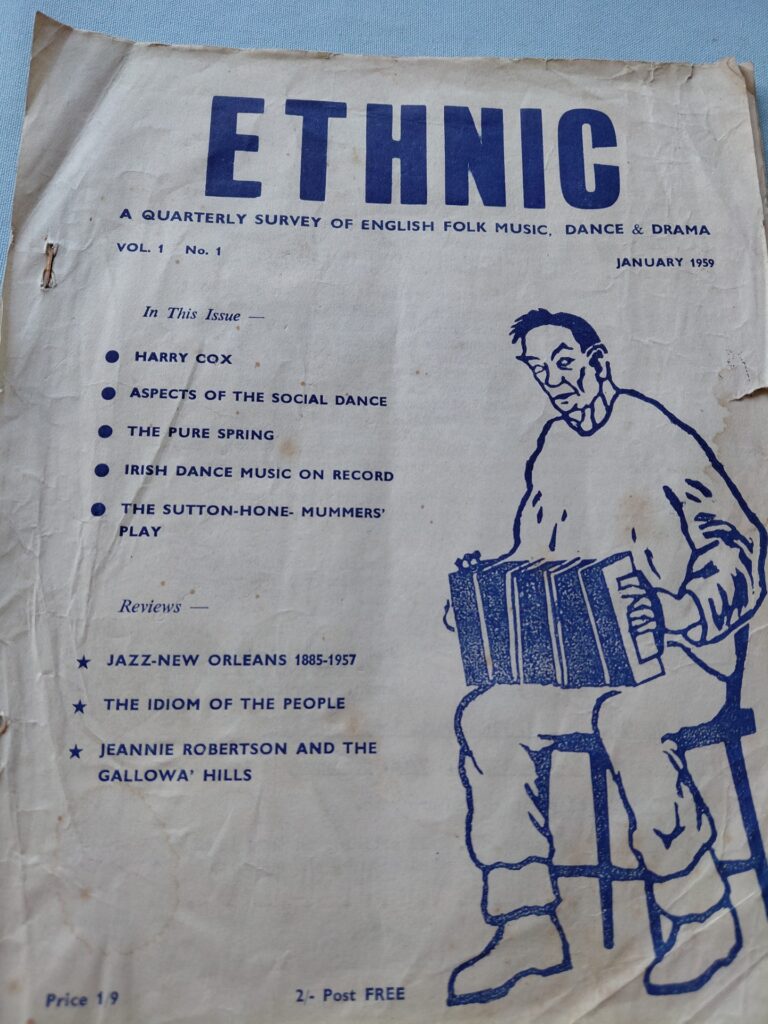

short-lived magazine, which ran to just four issues, was Ethnic magazine, edited by

Peter Grant, Reg Hall and Mervyn Plunkett. Later, Reg Hall wrote: “Mervyn Plunkett

(1920-86) tape recorded many singers and musicians in Sussex, Norfolk, Dorset,

Cornwall, Oxfordshire and Hampshire. He and I jointly produced four issues of Ethnic: A

Quarterly Survey of English Folk Music, Dance and Drama in 1959 and an EP 4 Sussex

Singers (Collector Records JEB7) in 1961, featuring George Spicer, Pop Maynard, Jean

Hopkins and Jim Wilson.” (1) Both men were involved in the West Hoathly Band of

Music, playing with the older pub musicians of that part of Sussex and, amongst other

things, brought the music of Norfolk’s Walter and Daisy Bulwer and Billy Cooper to a

wider audience. (2)

Ethnic magazine was a crude, basic affair by many standards. It contained no

photographs and comprised typed pages, with only the occasional drawing or diagram

amongst the text. The editorial policy statement read: “This Magazine is concerned with

traditional English song, instrumental music, dance, drama, and related activity and

custom. We hope to provide a common platform for singers, players, critics, collectors

and commentators who have the good of the tradition at heart.” In this respect, it

undoubtedly fulfilled a need in its short life. With this in mind, and given the rarity of

existing copies today, what follows is the article about Harry Cox, in the first issue, (3)

with the title given above, complete and without editing or abridging, including retaining

the occasional rendering of dialect speech, such as “hare” for “here”, as in the quote

above, also taken from the magazine, in a section entitled “Things They Say.” Unlike the

other articles in the rest of the magazine, no actual authorship is given.

———————————————————————————

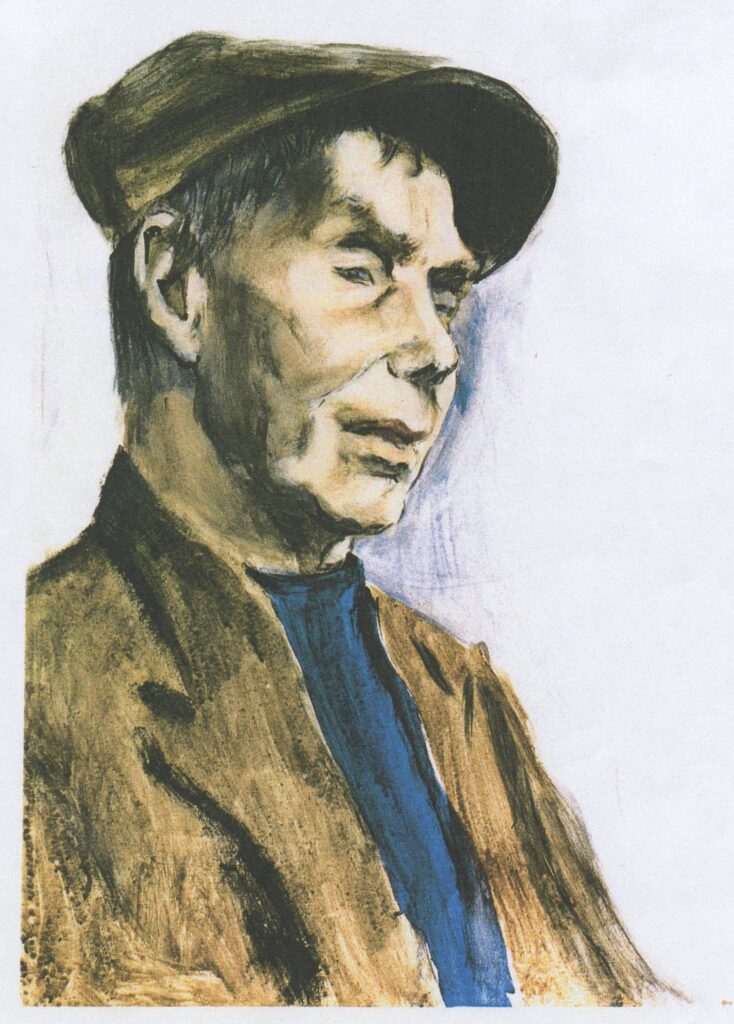

Harry Cox – The Catfield Wonder

No English folksinger has been more publicised than Harry Cox of Catfield, Norfolk. At

73 Harry is an almost legendary figure who for twenty years has been presented to us

as a relic miraculously preserved from a bygone age. Casual readers of the literature

during the thirties and forties might well have imagined that – apart from Philip Tanner of the Gower – Harry was the last of the Mohicans, and that with him would die the last

flicker of a fire that had burned throughout English history. Of course, people know

better now, and recognise that there are in fact several ancient English singers still

alive, or rather, lingering on.

While most field collectors would agree that there are still thousands of good traditional

singers in the countryside, Harry is widely regarded as the doyen of them all and the

post-War revival has brought him renewed recognition in the shape of BBC recording

sessions, television with Alan Lomax, and more recently a visit to the heart of

Revisionist Revivalism – the Hootingnanny. “The rummest do I bin to lately.”

Harry was born at Barton Turf on Barton Broad, one of a family of thirteen, of whom four

died in infancy. His grandfather was well known locally as a step-dancer and as a singer

with a very large repertoire. Harry learned many of his songs from him and will cite this

as evidence that some of his songs are more than a century old. In Harry’s childhood

his family had a bitter struggle to make ends meet, yet he is able to say of his

grandfather “he was in the hard times.” Harry’s father was a noted singer and fiddle

player – his fiddle was always in demand at festive occasions and in the local pubs –

and when money was short he could often earn as much as a day’s pay for an

evening’s playing, with beer thrown in. He would bring in as much as a shilling a night

when Harry was “a little old tot.” Unlike his father, who was a fisherman and wherryman, Harry has spent most of his life on land “doing everything I should think round about the farming way.” He has often been referred to as a blacksmith, but doesn’t know how the idea got about, “except maybe that I’m black enough.”

During the first World War Harry served on a minelayer in the North Sea, based on

Rosyth and Scapa Flow. Apart from this period and occasional trips to Norwich and

London, he has never been more than a few miles away from his home. He recalls one

visit to London on which he was pressed into playing the ‘house’ melodeon and came

home with full skin and pockets. In his experience strange musicians generally did

better than local men, and some of the travelling fiddle players at that time were

comparatively wealthy men. The dancing in the pubs was step and clog mixed in with

four-hand reels and other country dances.

“Polkas? I never was in that. These hare old women they used to like what they called a

jig – a jig-step they called it. These hare old girls they used to come in the pubs and

have a spree – used to kind of skip and mess about. The ‘Ship’ at Sutton was never a

real dancing house – not like some of the others – although we used to have our

meetings there and Moeran used to come. I never did know him before, myself. I think

his father was a clergyman over at Bacton. Then he was in the first World War – he

began collecting these songs before – then he had to pack up. After the War he began

again – he used to come to Sutton. Come that way I first met him. He put me in those

books. They never were all in there though. He did well, he did a lot of writing. You used

to sing for him – he used to get the music – take the tune down you see, a little in this

line, a little in that. He got the “Ploughboy.” I don’t know what happened to that – he sold that or something or other. He got ten pound for that. We went halves. Well, they can’t do what they like with these hare songs, really, can they? That was mine – or that was how he got it. We had five pound apiece. I don’t know what I done with it – where it went. Now I’m blessed. He was a good chap.

Harry is a modest and warm-hearted man of many skills. It is nearly fifty years now

since he made his “little old dancing doll.” This doll accompanied him on his recent trip

to London, but he didn’t unpack it. The doll is carved out of wood, blackened and

burnished by long years of handling. The body is supported by a horizontal peg which

projects from its back and is held rigidly in one hand. The arms and legs are freely

articulated in puppet fashion. The operator sits on one end of a thin three-foot board,

the other end projecting between the knees and free to vibrate vertically. The doll is held in position just above the free end of the board which is rapped with the knuckles of the free hand. The result is a spectacular quick-fire clog dance by the doll to a diddled accompaniment.

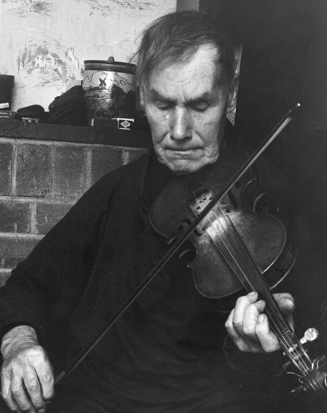

Harry plays the fiddle, but unlike his father he is very shy of playing it in public –

preferring to tune up in the afternoons when he is alone in the house. His main

instrument is the melodeon, which he plays with a fierce open four-in-a-bar left hand

and a jagged right – a rough and typically Southern style of great drive and punch. His

tune repertoire includes many old EFDS stalwarts and it is an eye-opener to hear these

tunes played in this earthy style. Although his playing gives the impression that he has

never been a player at formal dances, Harry does not regard his instrument as a vocal

prop – indeed he never accompanies himself when singing. This apparent dissociation

of instrumental music from song and organised dance is common amongst country

musicians.

Harry’s repertoire has never been fully documented, and the list, published in the current EFDS Journal (53 songs) falls a long way short of the 200 accredited to him by rumour. Gifted as he is with an ear which is both accurate and remarkably retentive, his total may well be over the two hundred mark. He can, for example, sing verses of songs which he has heard Bob Roberts sing a couple of times on the wireless and is keen to

acquire an additional verse or two for those of his ballads which he feels are not quite complete, or of which he says “I never did get that bit right.”

Of the fifty-odd songs I have heard him sing, almost all are in the major mode. Even the

exotic-sounding “Georgie” which starts off in the Dorian owes much of its attraction to a

late switch to the major. Few of his tunes show any marked tendency towards

hexatonism and he is no more disposed to sing in the Mixolydian than are other

traditional singers. He pitches mainly in the middle to lower register and would perhaps

sing a tone or so higher if his voice permitted him nowadays. Like that of every other

great country singer his style sounds deceptively simple and has little decoration. He

makes little use of the shake and decorates sparingly. His pitching is subtle, decorative

figures often being sharpened and line-endings flattened slightly, the effect being to give greater lift to the performance. While he does not slur to any marked extent, a

noticeable feature of Harry’s style is the quite artificial quality of many of his vowels and

most of his consonants.

Harry’s unnatural singing pronunciation is quite deliberate and is by now means unique.

It tends to give his words a curiously exaggerated clarity and to give added emphasis to

the beat. As he says himself, he likes a tune to have a swing to it. Many of his tunes are

very fine, but the impression given by the BBC recordings is misleading as these are

highly selected. Harry singing in the flesh and swapping songs as they come into his

head is not the rare and exotic flower of the fens – a great many of his songs are

common amongst my Sussex friends – but rather a homely and familiar figure as we

argue the toss as to whether Maria Martin and William Corder belong in the same song

as Maria Back and Switzerland John of “The Folkestone Murder.”

Harry is no orchid; nor a daisy for that matter. Perhaps his badge should be one of his

own beautiful corn-dollies, draped with a twist of duck-weed.

Schottische

I had a little horse

He was such a kick-er

I stuck a plaster to his arse

And made him kick the quicker

It was all done with sheepskin

Beeswax

Tons of pitch and plaster

The more you tried to pull it off

By God it stuck the faster

I had a little cat

He was such a thief Sir

Stuck a plaster on his arse

And pulled out all his teeth Sir

It was all done…etc

I had a little wife

She was very civ-il

Stuck a plaster to her arse

And drew her to the dev-il

It was all done with beeswax

Sheepskin

Tons of pitch and plaster

The more you tried to pull it off

By God it stuck the faster

The tune is close to “The Ball of Kirriemuir”

There Was an Old Woman in Yorkshire

There was an old man in Yorkshire she did dwell

She lov’d ‘er old husband dearly and the lodger twice as well

Tiddle dee whack rye diddle um day

Toora looral day

She went to the doctor’s and asked him all so kind

Which was the nearest way to send ‘er old husband blind

He told ‘er to get some marra bone an’ scrape it fine and small

Rubber it into the old man’s eyes till he can’t see at all

The old man said I’ll go ‘n’ drown myself for I can’t see one mite

The old woman said I’ll go with you ‘fraid you shouldn’t go right

Arm and arm they went on until they came to the brim

The old man ‘is foot to one side and plump’d the old woman in

She swam about and swam about until she came to the brim

The old man got the linen prompt and pushed ‘er further in

How the old woman did scream how the old woman did bawl

The old man said I can’t help you for I can’t see at all

So now my song is ended and I can’t sing no more

My old woman is drownded and I am safe on shore

Toora looral day

This song is sometimes known as “Johnny Sands.” It seems to be well known in Ireland

and in the States, and has been referred to as well-known in England. It does not,

however, appear to have been printed in any of the collections or in the EFDS Journal,

although it has appeared on broadsides.

Bold Archer

It was all in the month of June

Just as the flowers were in full bloom

A cas’ ‘e was built on Kansa’ Green

For to put Bold Archer in

So now our brother in prison do lay

Condemn’d for to die is he

If I ‘ad eleven such brothers as me

So soon a prisoner I’d set free

Oh eleven said Richard that’s little enow

For forty there must be

The chains and the bars will have to be broke

Before Bold Archer we can set free

Now ten for to stand by our horses rein

Ten for to guard us round about

Ten for to stand by the cas’le wall

And ten for to bring Bold Archer out

So Dickey broke locks and Dickey broke bars

Dickey broke everything he could see

He took Bold Archer under his arm

And carried him out most manfully

They mounted their horses away they did ride

Bold Archer he mounted so ‘appy and free

They rode till they came to a far waterside

Where they dismounted s’ manfully

And then they order’d the music to play

It played so sweet and joyfully

And the ver’ best dancer amongst them all

Was Bold Archer who they set free

Oh look back look back Bold Archer he cried

Look back look back cried he

Here comes the High Sh’reeve o’ Honny Dundee

With a hundred men in his company

Oh come back come back now cried the High Sh’reeve

Come back come back cried he

If you down retorn my irons to me

Bold Archer a prisoner still must be

Oh no nay no nay that never can be

No that never can be

The iron will do our horses to shoe

And the smith he’ll a-ride in our company

So ‘e wrote a letter home to ‘is wife

And to his children three

Say’ng my ‘orse is lame and I cannot swim

So condemn’d this day shall be

Note. We make no apologies for the printing of Harry’s “Bold Archer.” Verses 1- 7 of this

ballad were published by Francis Collinson and Francis Dillon in their collection of

songs from “Country Magazine” – (Songs From The Countryside, book 1, W. Paxton &

Co.) without acknowledgement of the source. Our version of Harry’s text differs

substantially in Verse 6, and we print the whole in order to do justice to a very fine and

otherwise unknown ballad.

Note. In spite of the association of Harry’s name with that of the late E J Moeran, the

latter included hardly any of his songs in his two contributions to the Folk Song Journal

(Vol. VII No. 26, 1922, & Vol. VIII No. 35, 1931). In those collections it will be seen that

Moeran relied almost entirely on material from other Norfolk and Suffolk singers. Very

few of Harry’s songs are available in print, but about fifty are available on disc

recordings in the Sound Library at Cecil Sharp House (BBC recordings). One master of

his “Foggy Dew” has been released twice by HMV in two different settings – one on LP

and one on EP (“The Barley Mow”).

Songs not listed in the EFDS Journal Vol. VIII No. 3 include –

Wreck of the Ramilles Rigs of the Time

Barbara Allen Box upon her Head

Outlandish Knight Lord Bateman

Jolly Cobbler I wish they’d do it now

Folkestone Murder Cruel Ship’s Carpenter

Miss Doxy Johnny used to grind the coffee mill

Hungry Fox One man to mow me down my meadow

———————————————————————————-

As mentioned previously, the above text has been given verbatim and complete, with no amendments made, to preserve fully the article in its original form. Fuller details of Harry Cox’s life and music are available in a variety of articles, including on this site, where can also be found a full discography of his recordings. Highly recommended too is the

Bonny Labouring Boy CD set released by Topic Records (TSCD512D) with its

accompanying booklet, and on which Bold Archer can be heard. Harry’s version of

There Was an Old Woman in Yorkshire (Marrowbones) was released on the English

Love Songs LP.

Chris Holderness August 2025

Notes:

(1) Reg Hall: “I Never Played to Many Posh Dances”: Scan Tester, Sussex Musician

1887-1972 Musical Traditions supplement no. 2 1990 p.69

(2) The English Country Music album, originally released as Record No.1 in 1965.

This will be considered in detail in a future article.

(3) Vol.1 No.1 January 1959